This is the first in a four-part blog post series offering strategies for increasing educational equity by reducing chronic absence.

By Hedy N. Chang, Executive Director and Founder, Attendance Works

Addressing today’s unprecedented levels of chronic absence in schools across the country is essential for ensuring all students have an equal opportunity to learn and thrive.

Chronic absence is defined as missing 10 percent or more of school for any reason. Left unaddressed, chronic absence can result in students struggling to read by grade 3, low academic achievement in middle school, and not graduating from high school.

National data show that nearly 14.7 million students (29.7%) were chronically absent in the 2021–22 school year, with roughly 6.5 million more students missing 10 percent or more of school days, when compared with the school year before the pandemic. Although available state data from SY 2022–23 show that chronic absence is starting to decline from its pandemic-impacted peak, it remains at staggeringly high levels.

Who is affected by chronic absence?

Chronic absence now affects the educational experience of most students in the United States—regardless of their ethnicity. When absenteeism reaches significantly high levels in a school, the educational experience of all students, not just those frequently missing school, is also affected. The churn in the classroom and the school affects teachers’ abilities to teach and establish classroom norms and makes it more difficult for students to learn. Research shows that elevated levels of chronic absence decrease achievement for all students.

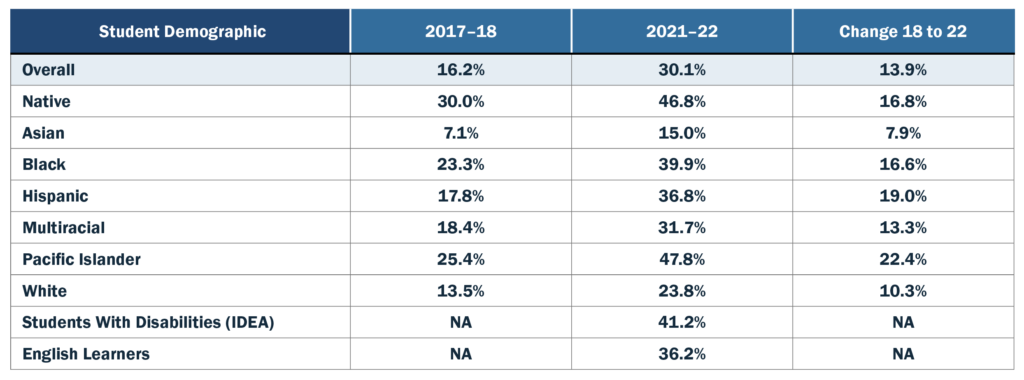

Before the pandemic, only a quarter (25%) of all enrolled students attended schools in which at least 20 percent of students were chronically absent. In SY 2021–22, two-thirds (66%) of enrolled students attended a school with such high chronic absence. In SY 2021–22, the largest number of chronically absent students were white (5.2 million), followed by Latino (5 million) and African American (2.9 million). National data shows that chronic absence is equally divided among male and female students. At the same time, much higher percentages of Native American, Hispanic, Pacific Islander, and Black students, as well as students with disabilities and English Learners, are chronically absent.

Table 1. Percentage of Population Who Are Chronically Absent

Note: https://weeac.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/WEEAC-Blog-From-Absences-to-Action-Appendix-03.11.ADA_FINAL.pdf

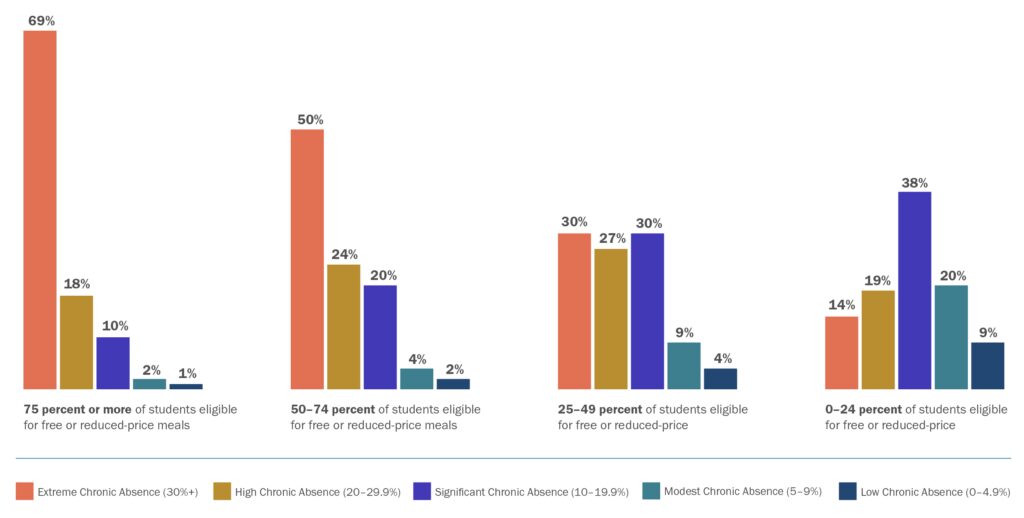

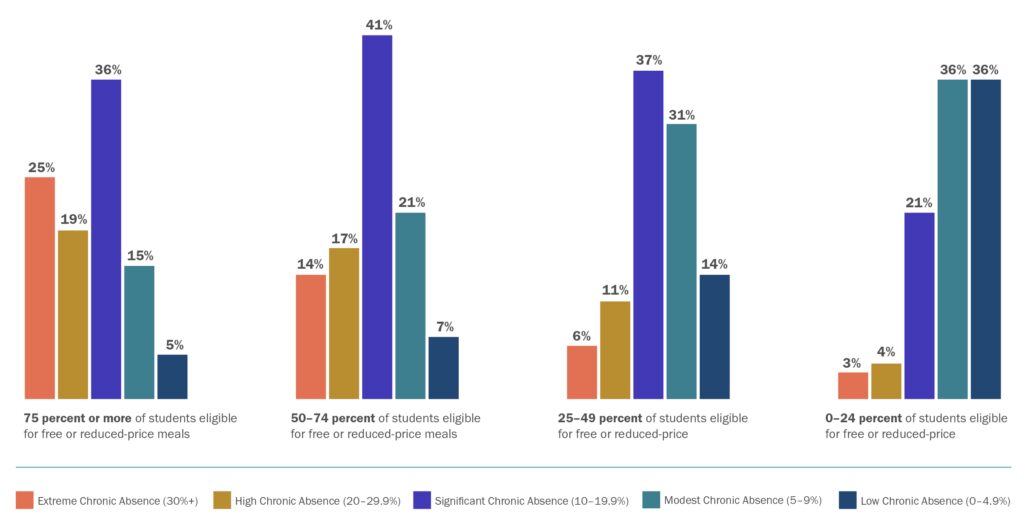

According to a 2021 Report by Attendance Works and the Everyone Graduates Center, students from populations with historically less access to educational opportunity are also much more likely to be enrolled in schools with extreme levels (greater than 30%) of chronic absence. Among schools with 75% or more of their students receiving free or reduced-price lunch (FRPL), schools with extreme chronic absence levels nearly tripled, from 25 percent in SY 2017–18 to 69 percent in SY 2021–22. Among schools with 50 percent to 75 percent FRPL, it increased from 14 percent to 50 percent. (See Charts 1 and 2.) Similar patterns hold for schools serving 75 percent or more students of color.

Figure 1. School Chronic Absence Levels by Concentration of Poverty, SY 2021–22

Defined as percent of students eligible for free- or reduced-price meals*

Note: https://weeac.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/WEEAC-Blog-From-Absences-to-Action-Appendix-03.11.ADA_FINAL.pdf#page=2

Figure 2. School Chronic Absence Levels by Concentration of Poverty, SY 2017–18

Defined as percent of students eligible for free- or reduced-price meals*

Note: https://weeac.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/WEEAC-Blog-From-Absences-to-Action-Appendix-03.11.ADA_FINAL.pdf#page=4

In addition, the most economically challenged districts are much more likely to have multiple schools with extreme levels of chronic absence than more affluent districts. For more information, see All Hands on Deck.

How do we address these unprecedented levels of chronic absence?

Districts, schools, and community agencies can embed the following strategies in their existing initiatives and operations to increase student attendance and engagement.

- Ensure actionable data. Because attendance data is collected daily, it is an invaluable tool for offering immediate and ongoing feedback. Chronic absence data, when disaggregated by grade, school, student group, and if possible, neighborhood, can be used to identify which students, student groups, and communities need more targeted resources and support and early intervention before situations are harder to resolve. But this can only occur when chronic absence data is accessible to the public, accurate, easy to understand, and timely.

- Change the blame mindset. Too often when absences start to add up, the initial reaction is to blame the child or their family for not caring enough to make school a priority. But, as this report by AIR and Attendance Works discusses, absences are caused by systemic challenges in the community that are beyond a student’s or family’s control (e.g., lack of access to health care, unreliable transportation, unstable housing, lack of safe paths to school) as well as in school (e.g., an unwelcoming school climate, biased disciplinary or attendance practices, or lack of a meaningful and culturally relevant curriculum). A blaming response can worsen the situation by causing the student and family to feel alienated, distrustful, and angry. This is especially the case if a student and family have experienced trauma, which this 2017 study appearing Academic Pediatrics shows is highly correlated to chronic absence.

Attendance can be improved by changing how we communicate with families about unexcused absences. This 2019 paper, Using Behavioral Insights to Improve Truancy Notifications, conducted in California, found that truancy notifications were much more effective when the notices did not begin with the state-mandated legalistic language or did not threaten punitive action. The more effective letters listed the specific days a student missed, offered clear information about the potential consequences of chronic absence on learning, the important role parents play in getting their children to school, and encouragement and support for parents and guardians to help their children get to school.

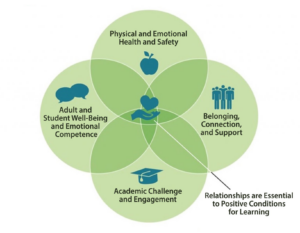

An essential element of changing mindsets is ensuring schools, districts, and communities invest in a multi-tiered approach that emphasizes prevention and early intervention where referral to the court system is used as a last resort. - Invest in relationship building and positive conditions for learning. As this article published in 2023 by the National School Boards of Education discusses, high levels of chronic absence in a school or district are a red flag that the positive conditions that motivate showing up to school have been eroded. These positive conditions for learning include healthy and safe school environments, a sense of belonging, connection, and support; academic challenge and engagement; and adult and student well-being and emotional competence.

Positive Conditions for Learning Lead to Students Being Engaged and Attending Regularly

© Attendance Works, attendanceworks.org

Relationship building is the most critical ingredient. An October 2023 analysis by Learning Heroes and TNTP found that schools with higher levels of family engagement had significantly lower increases in chronic absence during the pandemic. The positive impact of family engagement was greater for families with incomes below the poverty line. Attendance also reflects student connectedness. Students are connected to schools when they believe there is an adult at school who knows and cares about them, they have a supportive peer group, they engage at least some of the time in activities they find meaningful and that help others, and they feel seen and welcome in school. For example, having a teacher of the same racial background is associated with fewer unexcused absences. To be effective, engagement strategies must be culturally and linguistically appropriate for students and families. Attendance improves when districts ensure real-time communication in the family home language. - Partner with students and families to understand the challenges that cause absences and what helps them reengage and show up regularly. Improving student attendance requires understanding and addressing the root causes that lead to students’ missing school in the first place. Although some factors, such as school climate or attendance and discipline policies, are more within the locus of control of schools, others—for example, housing instability or community violence—are not easily addressed by school districts alone. When chronic absence affects larger numbers of students, it indicates challenges that require more systemic and programmatic solutions and the support of community partners.

Putting in place meaningful solutions requires deepening our understanding of what affects attendance for the student groups who make up the largest numbers of chronically absent students as well as those groups who are disproportionately affected by chronic absence. A variety of qualitative data collection methods (empathy interviews, surveys, focus groups) should be employed to gather insights directly from students and families. Tapping into student and family voices helps ensure that the engagement strategies are inclusive of students’ and families’ cultural norms. - Collaborate with community organizations and tribal governments. Helping students and families overcome attendance barriers requires strong and strategic collaboration with the agencies and organizations in your community who already know the languages and cultures of students and families. Such organizations might be able to offer resources (health care, mental health supports, housing, food, transportation, etc.) that can help families overcome obstacles that prevent their children from getting to school. For American Indian and Alaska Native students, reaching out to tribal governments is especially essential. Once you’ve identified the organizations, learn about each other and identify areas of common interest. Share data, as appropriate, on which students are chronically absent so that you can coordinate the needed outreach.

- Utilize teams at the district and school levels. Tackling chronic absence, especially when it affects significant numbers of students, is not a solo endeavor. It requires the support of district and school teams who have the insights, resources, and data needed to design, implement, and assess the effectiveness of activities and interventions. Such teams should not only focus on the case management of particular students but establish a strategic and systemic approach to improving attendance. Effective teams include members who reflect the demographics of the students and families served.

The continued high levels of chronic absence in schools across the country are an urgent call to action for all of us to work together to reengage our students and families and address the root causes of educational inequity occurring inside and outside of schools.

This product is prepared for the Western Educational Equity Assistance Center (WEEAC) at WestEd, which is authorized under Title IV of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and funded by the U.S. Department of Education. Equity Assistance Centers provide technical assistance and training to school districts and tribal and state education agencies to promote equitable education resources and opportunities regardless of race, sex, national origin, or religion. The WEEAC at WestEd partners with Pacific Resources for Education and Learning and Attendance Works to assist Alaska, American Samoa, Arizona, California, Colorado, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Hawaiʻi, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming.

The contents of this product were developed under a grant from the Department of Education. However, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the federal government.